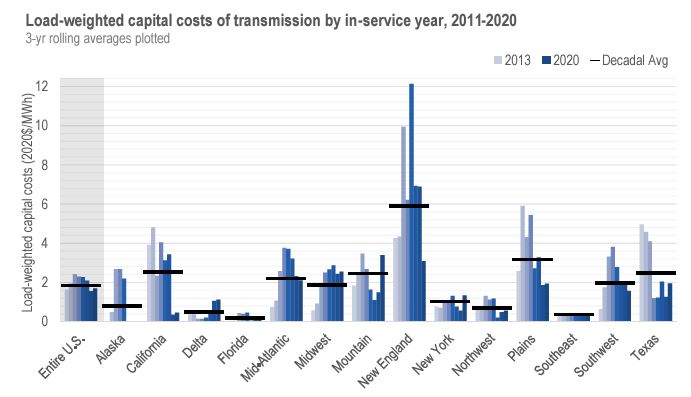

Gridlocked: Planning Failure with the Southeastern Regional Transmission Planning Process12/20/2023 The Southeastern Regional Transmission Planning (SERTP) process is run by some of the largest utilities in the southeast, including Duke Energy, Southern Company, Tennessee Valley Authority and others. For the past decade, SERTP has failed to provide any real regional transmission planning solutions. SERTP was never intended to be a true planning process and is riddled with flaws. SERTP officially began in 2013 as an effort for the non-organized southeast to comply with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission's newly minted Order 1000, which required improved regional transmission planning between utilities. The Department of Energy's latest National Transmission Needs Study found that the Southeast will need to expand its transmission capacity by 77% by 2035; however, even with the implementation of FERC Order 1000, this past decade has resulted in some of the lowest levels of investment in the Southeast compared to other regions around the country. An impediment described in the DOE report includes the lack of transparent locational energy pricing: "...information on the economic value of congestion outside RTOs/ISOs is minimal when compared with the market price differential data available from RTOs/ISOs..." As a result, "The Delta, Southeast, and Florida regions installed the fewest circuit-miles, relative to regional load, throughout the decade." Why does transparent locational energy pricing matter for transmission planning? In other regions, clear energy price differentials enable transmission planners to identify valuable transmission projects that would reduce overall system costs. Without energy pricing data, utilities in the south are effectively blindly managing generation dispatch to maintain system reliability, without consideration of ratepayer costs. There's always a cost, even if it's not accounted for. This year, SREA worked with other stakeholders in the SERTP Regional Planning Stakeholders Group (RPSG) to develop four out of the five scopes of work for the "Economic Planning Study" process. SERTP is a transmission planning process entirely run by the utilities, and we were appreciative for the opportunity to develop several studies. The process works like this: identify a source (usually a full balancing authority area), an amount of megawatts to move (this is non-resource specific, so the models don't know if the new megawatts are solar or coal), and a sink where the power is moved to (again, another balancing area). Plug those data into the models, and the models help identify problems on the grid that need to be resolved. Based on some significant transmission constraints in Northern Georgia that were described by Georgia Power Company in their 2022 IRP, we evaluated moving 1.6 GW (in our view, solar projects) from Southern Georgia to Northern Georgia, and another scenario that looked for the same amount from TVA into North Georgia. The results were quite good. The SERTP utilities estimate $96 million in upgrades to move 1.6 GW of power from the South to the North of Georgia, and just $56.5 million to move that amount of power from TVA. Several of the transmission constraints (thermal loadings) are already exceeding 100% even without the requested new power flows (the Charleston-Hiwassee River 161 kV line is already at 108.7% thermal loading without any changes), indicating TVA's system is already stressed and the costs associated with the study results are not necessarily driven by the new power flows represented in the RPSG studies. When considering that transmission substations can easily cost tens of millions of dollars, these results are stunningly good. Speaking of TVA, we requested an evaluation of moving 2.9 GW of power from Arkansas (MISO South) into Memphis. A few years ago, Memphis Light Gas & Water evaluated leaving TVA and joining MISO. For MLGW, it would have necessitated building or contracting with about 2.9 GW of new generation resources in Arkansas. At the time, MLGW estimated the new transmission costs would have been close to $376 million. While MLGW paused its efforts to evaluate MISO membership, the SERTP results suggest TVA could easily bring in 2.9 GW of power for $21.5 million - about 94% less cost than MLGW calculated. Given TVA's recent blackouts during Winter Storm Elliott, the company ought to seriously consider these minor transmission upgrades. Finally, SERTP evaluated importing 1,242 MW of power from MISO North into Louisville Gas & Electric/Kentucky Utilities (LGEKU). That analysis was based on LGEKU's recent requests to the Kentucky Public Service Commission to replace some existing coal-fired power plants with new natural gas units. The company did not consider MISO imports as an alternative; however, in the SERTP process, we were able to evaluate potential transmission limitations. Again, the SERTP analysis found it would be relatively low cost to upgrade the transmission system and enable the power flows: just $83.5 million. Will any of these transmission projects get built? It all comes down to benefit metrics: how do transmission planners view the value of transmission compared to the costs? SERTP is Ineffective While the SERTP analysis results were quite positive, the extent of SERTP's usefulness ends with the study results. Stakeholders were shocked to learn that the SERTP utilities evaluate no benefit metrics for the potential projects identified. Thus, the "Economic Planning Studies" truly evaluate no economic component of transmission planning, nor do the studies incorporate even the most basic values of transmission. None of the transmission identified is guaranteed to be in the utilities' actual transmission plans. There is a process where SERTP utilities can evaluate a benefit of transmission. SERTP, by its tariff rules, is only allowed to evaluate a single benefit metric: avoided transmission. If the SERTP utilities find a transmission project that they like in the SERTP process, they would evaluate any savings associated with cancelling potentially smaller planned projects nearby. By replacing smaller transmission projects with a more robustly planned project, the utilities would theoretically reduce costs and build the new line. But there are a few problems with this theory. First, SERTP only evaluates 10 years’ worth of benefits from the time the study begins. Thus, if a study begins in 2024, the analysis will only stretch out to 2034/2035. SERTP utilities often insert the new transmission assumptions perhaps 5-9 years into the process, meaning that potentially only a few years of transmission benefits are calculated. Put another way, if a transmission project gets added in the 9th year of a 10-year model, only 1-year of benefits are measured, even though transmission projects can easily last 40-60 years and provide numerous benefits during that time. The time horizon is unreasonably short. Next, many utilities may have 10-year transmission plans; however, those same plans are typically most accurate for the first five years, with the later years not fully vetted. In this case, a transmission project is only evaluated after year 7 or 8 in the model, but the utilities' internal plans effectively only go to year 5. Therefore, no transmission would be avoided by the new proposed line. There are no benefits to measure. SERTP's shell-game has never led to new transmission being built. This year, the SERTP utilities opted to not even bother to perform this additional analysis. It's no wonder why the SERTP process has never led to any regional or interregional transmission development. The process was designed to fail from the beginning. SERTP Isn't Accurate Transmission planning incorporates two fundamental data sets: generation and load (power demand). By modeling where new generation will be installed, or older generation will be retired, in addition to any load growth or decline, transmission planners are meant to find any potential reliability problems caused by the ever-changing system. Once the problems are identified, solutions can be built. In SERTP, the participating utilities share data with neighboring utilities - a sort of data swap to ensure that one utility's plans aren't going to negatively affect someone else’s in the footprint. If utilities aren't sharing accurate data, transmission modeling will not be able to identify potential problems ahead of time. Recently, LGEKU received approvals from the Kentucky Public Service Commission to retire nearly 600 MW of coal, build a 640 MW of new natural gas capacity, as well as build nearly 800 MW of solar plus 125 MW/500 MWh of battery storage. In essence, LGEKU is undergoing some pretty dramatic changes over the next few years. However, LGEKU representatives told their SERTP neighbors that the utility expects no "change throughout the ten-year planning horizon for the 2024 SERTP Process." (slide 188). When asked about this discrepancy, LGEKU representatives stated that the solar facilities had not yet received their Generation Interconnection Agreements, despite being approved by the PSC, and so the company (using their own internal "best practices"), decided to not include those changes. By the way, LGEKU is in charge of its own generation interconnection process and approvals, so any delays are caused by the company itself. Duke Energy in the Carolinas performs a different type of analytical gymnastics. The company there knows it wants to retire some existing generation resources, like Cliffside 5, Marshall 1 & 2, Roxboro and Mayo. When transmission planners remove electric generation in the models, the entire system responds to those retirements by ramping up generation elsewhere. This change in the power flow can result in transmission constraints: problems that need to be solved. Instead of letting the models work, Duke inputs "proxy" generators into the model to make up for the retirements. Duke explains that through this process, "Generators [are] left in [the] model in expectation of replacement generation through the Generation Replacement Request process." In other words, the model is told there is no retirement and are unable to identify if any problems would arise from the retirements. This is a form of hardwiring power plants into the model. By hardwiring “no change” into the models, it biases transmission planning towards the status quo and increases the likelihood that a utility will install a natural gas unit. Observant readers would note here that Duke has not received state regulatory approvals to replace those specific units at those specific sites and includes the changes anyway, while LGEKU has received approvals but does not include the changes in their models. When asked about the discrepancy in which units to include versus exclude, the SERTP utilities explained that each utility comes up with their own methods of data reporting. The individual utility methodologies are not consistent. This "best practice" method evidently also extends to load growth projections as well, meaning state integrated resource plans (which include both generation and load assumptions) are not necessarily included in the SERTP process. Perhaps the most egregious lack of data transparency and transfer in SERTP is with the Tennessee Valley Authority. Like LGEKU, TVA reported to its SERTP neighbors that the company expects no changes over the next decade (slide 261). In May 2023, TVA CEO Jeff Lyash told his board of directors that after a successful competitive solicitation, the company plans to sign contracts for 6,000 megawatts of clean energy resources from 40 solar farms. Those contracts would go a long way to meeting TVA's own goal of adding 10,000 megawatts of solar by 2035. Meanwhile, TVA told the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) that the company will "add 7,251 MW of natural gas generation and retire 5,159 MW of coal generation over the period. A total of 3,937 MW of [Bulk Electric System]-connected Tier 1 solar PV projects are expected in the next 10 years." TVA is telling its Board of Directors (its regulators), NERC, and SERTP utilities three different stories over the next ten years. When asked about these discrepancies, SERTP utilities explained that each utility comes up with its own methodologies for sharing data, or not. There are no rules regarding what gets included, or not. SERTP Ignores Public Policy As part of the SERTP process, stakeholders are allowed to ask that the utilities include a public policy scenario. Stakeholders are required to file their scenario request 60 days after the Q4 meeting, usually about a month before the Q1 meeting the following year. In 2023, three public policy requests were filed by stakeholders regarding North Carolina's Carbon Plan, a legally binding state public policy. At the Q1 2023 meeting, stakeholders were told that the SERTP utilities were still "evaluating" these requests and would provide an update at the next meeting. At the Q2 2023 meeting, SERTP utilities explained that they would not be performing a public policy analysis because, "SERTP itself has no role in the North Carolina local transmission planning process." In effect, the SERTP utilities have eliminated any state public policy for future discussions. In its order adopting the Carbon Plan, the North Carolina Utilities Commission stated that, "Furthermore, based upon the potential magnitude of future transmission expenditures, the Commission urges Duke to explore all possible efficiencies and to be vigilant in its participation in SERTP and in its coordination with PJM to assure a least cost path to achieve the carbon dioxide emissions reduction requirements while maintaining and improving reliability." Evidently Duke can unilaterally ignore its regulators, and the SERTP public policy process, and stakeholders have no recourse. To date, roughly a decade after FERC Order 1000 outlined a role for including state public policy in transmission planning, SERTP has never modeled a public policy scenario. Fixing SERTP SERTP exists because of FERC Order 1000, requiring regional coordination in transmission planning. In recent years, FERC has again taken up the prospect of developing a more holistic regional planning effort. FERC's proposed regional transmission planning rule, if applied to non-RTO regions like the southeast, would greatly improve SERTP's planning process. The planning rule borrows some of the (true) best practices of other regions by requiring multi-scenario, multi-value (benefits) analysis. Unsurprisingly, utilities in the southeast opposed FERC's proposed transmission planning rules, arguing in part that because the states do IRPs and SERTP works fine, FERC should not impose the transmission rule on the southeast. SREA's comments to FERC call into question the validity of the IRPs and SERTP. Given that even IRPs are not directly included in SERTP (nor public policies, nor some state approved contracts), it appears that the SERTP utilities had not been entirely straightforward with FERC. The SERTP utilities also told the Department of Energy to ignore the region. The utilities told the DOE Transmission Needs Study team that, “SERTP Sponsors also disagree with the Study’s claims that the Southeast will need a lot more transmission capacity in the future, as it does not have enough evidence to support this assertion. SERTP Sponsors claim that the Southeast already has a strong transmission system and has been investing in it to meet the needs of customers and to accommodate state energy policies.” However, the DOE Needs Study found that the Southeast has been one of the lagging regions in transmission development in the country. While a new FERC transmission planning rule that applies to the southeast would be exceptionally helpful, the rule only applies to a few utilities in the southeast. Duke, LGEKU, OVEC, and Southern Companies are considered the "Jurisdictional SERTP Sponsors", while Associated Electric Cooperative Inc. (“AECI”), Dalton Utilities (“Dalton”), Georgia Transmission Corporation (“GTC”), the Municipal Electric Authority of Georgia (“MEAG”), PowerSouth Energy Cooperative (“PowerSouth”), and the Tennessee Valley Authority (“TVA”) are all non-jurisdictional utilities. Those utilities participate in SERTP voluntarily and are outside FERC’s jurisidiction. For utilities like TVA, their board of directors would need to get serious about their job as regulators and require TVA to engage in SERTP earnestly. Alternatively, the United States Congress could amend the TVA Act of 1935 and require that TVA become FERC-jurisdictional. Absent FERC or congressional action, state regulators have an important role to play. Based on SREA's experience with SERTP over the years, it was rare for any state regulatory agency to ever attend SERTP meetings. When we mentioned this lack of regulatory oversight at SERTP, regulators often lamented not having enough time, nor enough qualified staff to engage in the transmission planning forum. While both may be true, it only underscores the importance of having robust stakeholder engagement. Stakeholders can sometimes help fill in the information sharing gaps and alert regulators to contradictory behaviors. State regulators no longer have the luxury of ignoring SERTP or the transmission planning processes of their utilities. The North Carolina Utilities Commission recently pushed for a series of transmission planning reforms. The reformed the North Carolina Transmission Planning Collaborative will soon become the Carolinas Transmission Planning Collaborative. There, the CPTC includes "...the Multi-Value Strategic Transmission (MVST) planning process. The MVST process 1) adopts a forward-looking/ proactive approach, 2) uses a scenario based approach to account for different possible futures, 3) accounts for multiple benefits, 4) avoids line-specific assessments and piecemeal planning, and 5) allows for meaningful stakeholder input into the process." Many of these requirements are based off the FERC proposed transmission planning rule. The process includes a Transmission Advisory Group (TAG) for stakeholders to be engaged. However, if stakeholders propose a scenario that "is more Regional in nature", stakeholders are pointed back to filing a request in SERTP. Individual states can make great strides in improving their own backyard transmission planning rules, but the regional and interregional aspects of transmission planning in the southeast are still entirely dependent on broken SERTP process. To fully fix SERTP, a Multi-Regulatory Strategic Planning Process is needed that includes FERC, Congress, and the State PSC's towards a shared goal of a more robust grid. AuthorSimon Mahan is the Executive Director of the Southern Renewable Energy Association.

0 Comments

|

Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed